I was once an artist of not insignificant renown, but my fame has since fallen into the abyss of time. If today you were to hear my name spoken, or come across it printed in a book, you would, my friend, think nothing of it.

I am nothing of it.

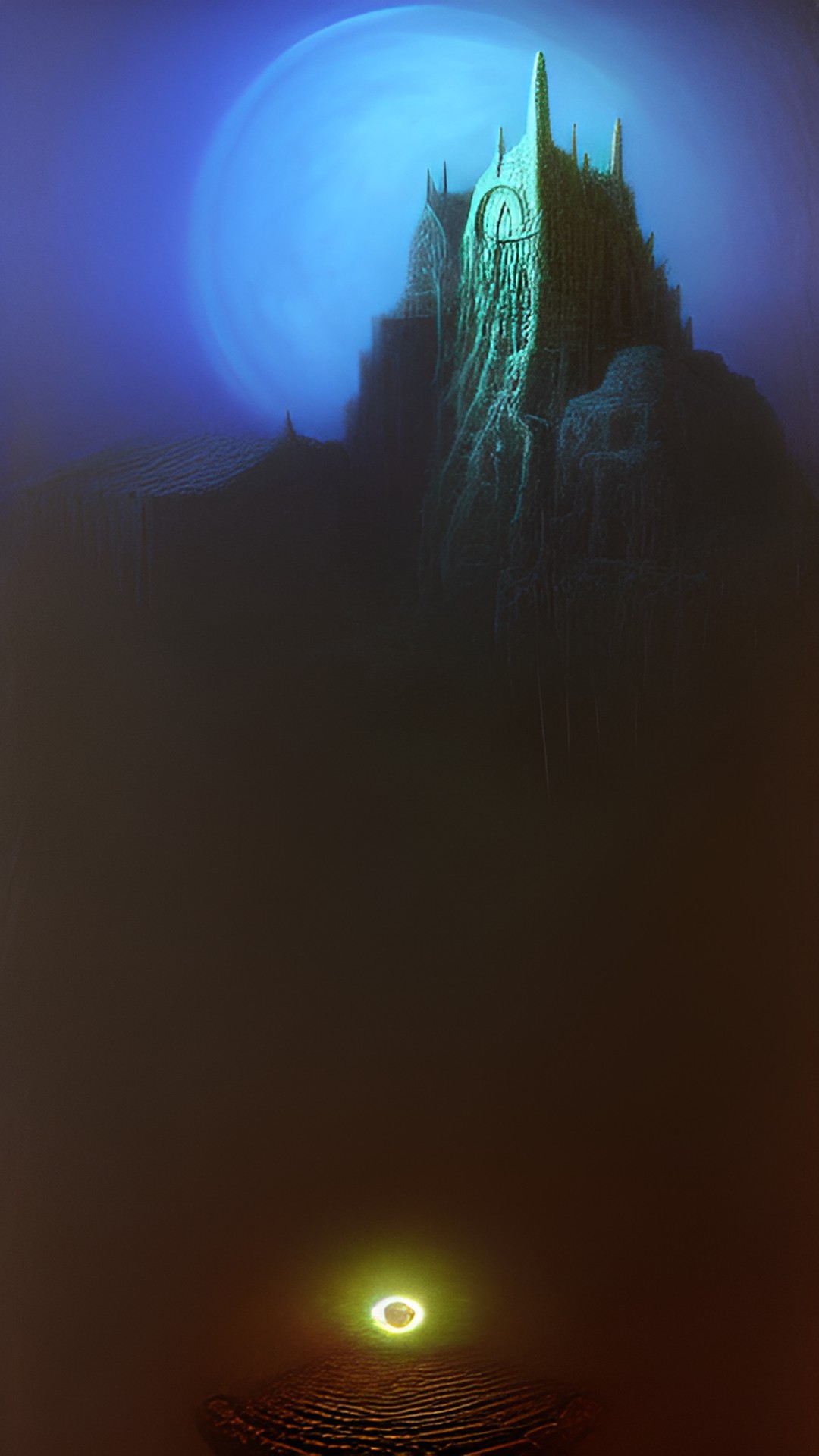

Ever since the castle, I am—ghosts, how I wish I never would have imagined its hideous visage, as black nearly as night, with its uppermost section only smeared with the pale, sickly green of the nethermoon. The entire massive construction, if it were indeed constructed, a conclusion I increasingly believe to be unsound, an unholy and incestuous progeny of cobwebs bred with tentacles. A petrified monstrosity. It is a mountainhouse. A dreadcomplex that with its growths and anti-angles mocks the science of physics itself.

I saw it first in a sketch I’d made, a still life, vase with apples and flowers, and from between my charcoal lines it emerged like a worm slithering from a rotting fruit.

As soon as I saw it, I knew I must draw it, and so with violent strokes as sure and bold as any I had made, I emerged it from the canvas—pulled it up like a weed, fished it out like a carcass, delivered it like a stillborn fetus.

Then I painted it.

The canvas was a bandage wrapped tightly around the frame; the castle, an infected gash; and the pigments, blood, seeping into and saturating it.

By the time I had finished, in one sleepless stretch of fevered days and nights, the completed painting had swollen so much in weight, in disproportion to its moderate size, I could barely lift it. But the ghastly image had already imprinted itself upon me. To think: I was then satisfied with my creation, with its faithfulness to the picture in my mind, transferred, or so I foolishly believed, to the flat reality of canvas, and with its unlikeness to anything I had created before. I understand now that I had whored myself to novelty and thus unleashed a demon…

Upon showing my painting of the castle to my usual buyers, I was as stunned by their reaction as they were by the artwork. “Have you a jest at my expense?” one asked in accusation.

“Not at all.”

“But you cannot in good faith expect me to purchase this—” “I understand, it differs from my usual work in content and style.” “—this… this empty canvas!”

Empty canvas?

Never had a canvas been as full! “But the castle,” I pleaded, pointing at it, tracing its inarchitected contours. “You must see the castle.”

“There is no castle.”

“There is. Here,” I said in rising anger, tapping the canvas, its paints still moist to the touch.

Alas, no one saw the castle except for me—and I began to see it everywhere: not only on the canvas but before my bloodshot eyes when I closed them to seek the sleep I could no longer find, and on every page of my sketchbook, and on every other canvas I had ever painted and in everything new I tried desperately to paint! Once I had been full of images. My talent was in releasing them. Now, there was only one, and how terribly it mocked me! by forcing me to remain its ossiferous cage.

I stopped going outside.

I responded to letters with the same single sentence. I cannot, as I am still painting the castle. I cannot as I am still, painting the castle. I cannot as I am: still, painting the castle I cannot. As I am, still painting, the castle, I…

I do not remember suffering the bout of hysteria, screaming the derangements quoted to me at the medical hearing, assaulting the man who had entered my home to subdue me before I was able to plunge the stiletto into my eye, but what I remember, I have been told, has no bearing on the truth. The truth and I have been separated from one another. That’s what happens to whores, a man hissed at me from the street. I was deemed an unreliable witness in the trial of my own sanity, which resulted in a finding that I am in possession—no one—of an unsound—sees—mind—the castle—hahaha!

Hahaha!

The sirens sound like laughter sometimes, don’t they? The doctors sound like train tracks being built.

I hate them all. They’ve no eye for art—for beauty. They dourly collect their observations, dressed in their little white frocks with faint pink stains that never come out, and apply them to the rubrics written for them by black gloved sodomites, arriving at diagnoses the way bankers arrive at usury: by precognitive design. They are blunt instruments. Rusted scalpels. Unsound mind! How dare they, who’ve no longer any minds at all, pronounce with despicable pagentriocious solemnity upon the state of mine. What is a sound mind, I put it to them. During the trial I yelled it: define a soundness of mind! Most sound is noise. They wouldn’t answer, the empty headed weasels. Cacophony is what they crave. Unsoundness is silence, contemplation, self-reflection, which presupposes a self, and you are unselves! I screamed at them. That’s why they dragged me away. I painted the castle!

They wrapped me in bandages and packed me into a carriage next, and the horses dragged us out of the city and up into the mountains. They had forced a cloth into my mouth to keep me quiet, but they took it out once I nodded that I would behave myself.

“Where are we going?” I asked.

“The sanctuary.”

“And just what’s that?”

“It’s a place where they make people better.”

“Is it so far away, so distant—so that no one can hear all the screaming!”

“Behave now.”

The horses’ hooves went clickety clickety clack, clickety clickety clack. “It won’t be far now,” they said. “You’ll see it as we take the bend here.”

Dear friend, how horrible was the revelation, for as the horses made their turn, I saw ahead of us the very castle I had painted!

“Do you see that?” I demanded. “Do you see the castle? It’s not a blank canvas, is it? Is it! There was no jest made at your expense, except God’s in making your stupidity—”

They forced the cloth back in my mouth, but it did not matter. The terror I felt was overwhelming. I cannot begin to describe the inner depths from which it emanated, bubbling up, a gelatinous lust for death; before popping like: an eviscerated eardrum, an overinflated eyeball, an all-correlating mind.

Every detail, each degenerate brush stroke, was now spawned before me. The sun itself appeared to hurry from the sky, to be replaced by the dreadmoon, in whose wicked wan light the image was complete—almost, for I was certain one detail was missing: a sole dab of paint near the top of the castle proper, and as the carriage rumbled on along the hard dirt road,

I knew that dab was me.